Gamma rays, also known as gamma radiation, refers to electromagnetic radiation (no rest mass, no charge) of a very high energies. Gamma rays are high-energy photons with very short wavelengths and thus very high frequency. Since the gamma rays are in substance only a very high-energy photons, they are very penetrating matter and are thus biologically hazardous. Gamma rays can travel thousands of feet in air and can easily pass through the human body.

Gamma rays are emitted by unstable nuclei in their transition from a high energy state to a lower state known as gamma decay. In most practical laboratory sources, the excited nuclear states are created in the decay of a parent radionuclide, therefore a gamma decay typically accompanies other forms of decay, such as alpha or beta decay.

Radiation and also gamma rays are all around us. In, around, and above the world we live in. It is a part of our natural world that has been here since the birth of our planet. Natural sources of gamma rays on Earth are inter alia gamma rays from naturally occurring radionuclides, particularly potassium-40. Potasium-40 is a radioactive isotope of potassium which has a very long half-life of 1.251×109 years (comparable to the age of Earth). This isotope can be found in soil, water also in meat and bananas. This is not the only example of natural source of gamma rays.

Discovery of Gamma Rays

Gamma rays were discovered shortly after discovery of X-rays. In 1896, French scientist Henri Becquerel discovered that uranium minerals could expose a photographic plate through another material. Becquerel presumed that uranium emitted some invisible light similar to X-rays, which were recently discovered by W.C.Roentgen. He called it “metallic phosphorescence”. In fact, Henri Becquerel had found gamma radiation being emitted by radioisotope 226Ra (radium), which is part of the Uranium series of uranium decay chain.

Gamma rays were first thought to be particles with mass, for example extremely energetic beta particles. This opinion failed, because this radiation cannot be deflected by a magnetic field, what indicated they had no charge. In 1914, gamma rays were observed to be reflected from crystal surfaces, proving they must be electromagnetic radiation, but with higher energy (higher frequency and shorter wavelengths).

Characteristics of Gamma Rays / Radiation

- Gamma rays are high-energy photons (about 10 000 times as much energy as the visible photons), the same photons as the photons forming the visible range of the electromagnetic spectrum – light.

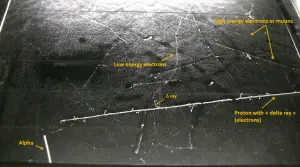

- Photons (gamma rays and X-rays) can ionize atoms directly (despite they are electrically neutral) through the Photoelectric effect and the Compton effect, but secondary (indirect) ionization is much more significant.

- Gamma rays ionize matter primarily via indirect ionization.

- Although a large number of possible interactions are known, there are three key interaction mechanisms with matter.

- Photoelectric effect

- Compton scattering

- Pair production

- Gamma rays travel at the speed of light and they can travel thousands of meters in air before spending their energy.

- Since the gamma radiation is very penetrating matter, it must be shielded by very dense materials, such as lead or uranium.

- The distinction between X-rays and gamma rays is not so simple and has changed in recent decades. According to the currently valid definition, X-rays are emitted by electrons outside the nucleus, while gamma rays are emitted by the nucleus.

- Gamma rays frequently accompany the emission of alpha and beta radiation.

Photoelectric Effect

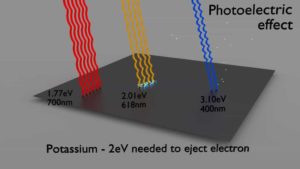

- The photoelectric effect dominates at low-energies of gamma rays.

- The photoelectric effect leads to the emission of photoelectrons from matter when light (photons) shines upon them.

- The maximum energy an electron can receive in any one interaction is hν.

- Electrons are only emitted by the photoelectric effect if photon reaches or exceeds a threshold energy.

- A free electron (e.g. from atomic cloud) cannot absorb entire energy of the incident photon. This is a result of the need to conserve both momentum and energy.

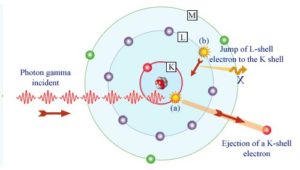

- The cross-section for the emission of n=1 (K-shell) photoelectrons is higher than that of n=2 (L-shell) photoelectrons. This is a result of the need to conserve momentum and energy.

Definition of Photoelectric effect

In the photoelectric effect, a photon undergoes an interaction with an electron which is bound in an atom. In this interaction the incident photon completely disappears and an energetic photoelectron is ejected by the atom from one of its bound shells. The kinetic energy of the ejected photoelectron (Ee) is equal to the incident photon energy (hν) minus the binding energy of the photoelectron in its original shell (Eb).

Ee=hν-Eb

Therefore photoelectrons are only emitted by the photoelectric effect if photon reaches or exceeds a threshold energy – the binding energy of the electron – the work function of the material. For gamma rays with energies of more than hundreds keV, the photoelectron carries off the majority of the incident photon energy – hν.

Following a photoelectric interaction, an ionized absorber atom is created with a vacancy in one of its bound shells. This vacancy is will be quickly filled by an electron from a shell with a lower binding energy (other shells) or through capture of a free electron from the material. The rearrangement of electrons from other shells creates another vacancy, which, in turn, is filled by an electron from an even lower binding energy shell. Therefore a cascade of more characteristic X-rays can be also generated. The probability of characteristic x-ray emission decreases as the atomic number of the absorber decreases. Sometimes , the emission of an Auger electron occurs.

Cross-Sections of Photoelectric Effect

At small values of gamma ray energy the photoelectric effect dominates. The mechanism is also enhaced for materials of high atomic number Z. It is not simple to derive analytic expression for the probability of photoelectric absorption of gamma ray per atom over all ranges of gamma ray energies. The probability of photoelectric absorption per unit mass is approximately proportional to:

τ(photoelectric) = constant x ZN/E3.5

where Z is the atomic number, the exponent n varies between 4 and 5. E is the energy of the incident photon. The proportionality to higher powers of the atomic number Z is the main reason for using of high Z materials, such as lead or depleted uranium in gamma ray shields.

Although the probability of the photoelectric absorption of gamma photon decreases, in general, with increasing photon energy, there are sharp discontinuities in the cross-section curve. These are called “absoption edges” and they correspond to the binding energies of electrons from atom’s bound shells. For photons with the energy just above the edge, the photon energy is just sufficient to undergo the photoelectric interaction with electron from bound shell, let say K-shell. The probability of such interaction is just above this edge much greater than that of photons of energy slightly below this edge. For gamma photons below this edge the interaction with electron from K-shell in energetically impossible and therefore the probability drops abruptly. These edges occur also at binding energies of electrons from other shells (L, M, N …..).

Compton Scattering

Key characteristics of Compton Scattering

- Compton scattering dominates at intermediate energies.

- It is the scattering of photons by atomic electrons

- Photons undergo a wavelength shift called the Compton shift.

- The energy transferred to the recoil electron can vary from zero to a large fraction of the incident gamma ray energy

Definition of Compton Scattering

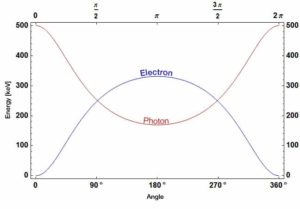

Compton scattering is the inelastic or nonclassical scattering of a photon (which may be an X-ray or gamma ray photon) by a charged particle, usually an electron. In Compton scattering, the incident gamma ray photon is deflected through an angle Θ with respect to its original direction. This deflection results in a decrease in energy (decrease in photon’s frequency) of the photon and is called the Compton effect. The photon transfers a portion of its energy to the recoil electron. The energy transferred to the recoil electron can vary from zero to a large fraction of the incident gamma ray energy, because all angles of scattering are possible. The Compton scattering was observed by A. H.Compton in 1923 at Washington University in St. Louis. Compton earned the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1927 for this new understanding about the particle-nature of photons.

Compton Scattering Formula

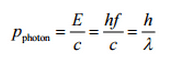

The Compton formula was published in 1923 in the Physical Review. Compton explained that the X-ray shift is caused by particle-like momentum of photons. Compton scattering formula is the mathematical relationship between the shift in wavelength and the scattering angle of the X-rays. In the case of Compton scattering the photon of frequency f collides with an electron at rest. Upon collision, the photon bounces off electron, giving up some of its initial energy (given by Planck’s formula E=hf), While the electron gains momentum (mass x velocity), the photon cannot lower its velocity. As a result of momentum conservetion law, the photon must lower its momentum given by:

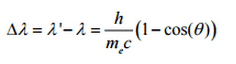

So the decrease in photon’s momentum must be translated into decrease in frequency (increase in wavelength Δλ = λ’ – λ). The shift of the wavelength increased with scattering angle according to the Compton formula:

Source: hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu

where

λ is the initial wavelength of photon

λ’ is the wavelength after scattering,

h is the Planck constant = 6.626 x 10-34 J.s

me is the electron rest mass (0.511 MeV)

c is the speed of light

Θ is the scattering angle.

The minimum change in wavelength (λ′ − λ) for the photon occurs when Θ = 0° (cos(Θ)=1) and is at least zero. The maximum change in wavelength (λ′ − λ) for the photon occurs when Θ = 180° (cos(Θ)=-1). In this case the photon transfers to the electron as much momentum as possible.The maximum change in wavelength can be derived from Compton formula:

The quantity h/mec is known as the Compton wavelength of the electron and is equal to 2.43×10−12 m.

Compton Scattering – Cross-Sections

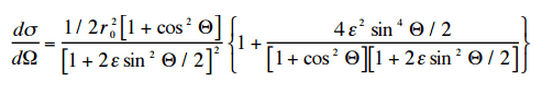

The probability of Compton scattering per one interaction with an atom increases linearly with atomic number Z, because it depends on the number of electrons, which are available for scattering in the target atom. The angular distribution of photons scattered from a single free electron is described by the Klein-Nishina formula:

where ε = E0/mec2 and r0 is the “classical radius of the electron” equal to about 2.8 x 10-13 cm. The formula gives the probability of scattering a photon into the solid angle element dΩ = 2π sin Θ dΘ when the incident energy is E0.

Source: hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/

Compton Edge

In spectrophotometry, the Compton edge is a feature of the spectrograph that results from the Compton scattering in the scintillator or detector. This feature is due to photons that undergo Compton scattering with a scattering angle of 180° and then escape the detector. When a gamma ray scatters off the detector and escapes, only a fraction of its initial energy can be deposited in the sensitive layer of the detector. It depends on the scattering angle of the photon, how much energy will be deposited in the detector. This leads to a spectrum of energies. The Compton edge energy corresponds to full backscattered photon.

Inverse Compton Scattering

Inverse Compton scattering is the scattering of low energy photons to high energies by relativistic electrons. Relativistic electrons can boost energy of low energy photons by a potentially enormous amount (even gamma rays can be produced). This phenomenon is very important in astrophysics.

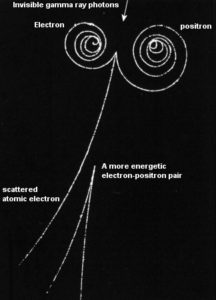

Positron-Electron Pair Production

In order for electron-positron pair production to occur, the electromagnetic energy of the photon must be above a threshold energy, which is equivalent to the rest mass of two electrons. The threshold energy (the total rest mass of produced particles) for electron-positron pair production is equal to 1.02MeV (2 x 0.511MeV) because the rest mass of a single electron is equivalent to 0.511MeV of energy.

If the original photon’s energy is greater than 1.02MeV, any energy above 1.02MeV is according to the conservation law split between the kinetic energy of motion of the two particles.

The presence of an electric field of a heavy atom such as lead or uranium is essential in order to satisfy conservation of momentum and energy. In order to satisfy both conservation of momentum and energy, the atomic nucleus must receive some momentum. Therefore a photon pair production in free space cannot occur.

Moreover, the positron is the anti-particle of the electron, so when a positron comes to rest, it interacts with another electron, resulting in the annihilation of the both particles and the complete conversion of their rest mass back to pure energy (according to the E=mc2 formula) in the form of two oppositely directed 0.511 MeV gamma rays (photons). The pair production phenomenon is therefore connected with creation and destruction of matter in one reaction.

Positron-Electron Pair Production – Cross-Section

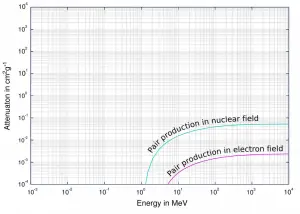

The probability of pair production, characterized by cross section, is a very complicated function based on quantum mechanics. In general the cross section increases approximately with the square of atomic number (σp ~ Z2) and increases with photon energy, but this dependence is much more complex.

Gamma Rays Attenuation

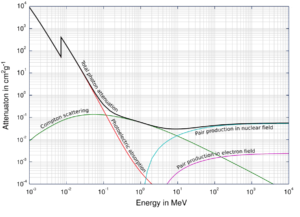

The total cross-section of interaction of a gamma rays with an atom is equal to the sum of all three mentioned partial cross-sections:

σ = σf + σC + σp

- σf – Photoelectric effect

- σC – Compton scattering

- σp – Pair production

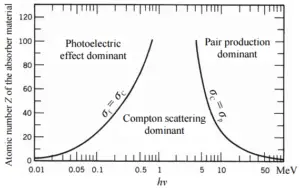

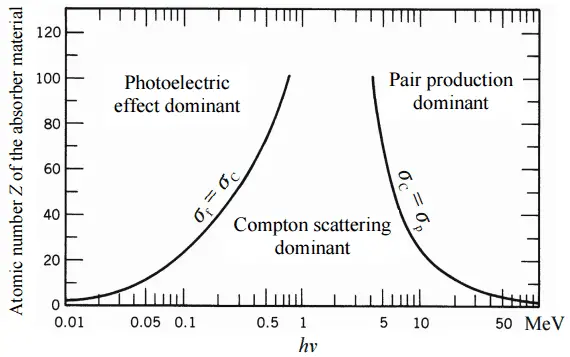

Depending on the gamma ray energy and the absorber material, one of the three partial cross-sections may become much larger than the other two. At small values of gamma ray energy the photoelectric effect dominates. Compton scattering dominates at intermediate energies. The compton scattering also increases with decreasing atomic number of matter, therefore the interval of domination is wider for light nuclei. Finally, electron-positron pair production dominates at high energies.

Based on the definition of interaction cross-section, the dependence of gamma rays intensity on thickness of absorber material can be derive. If monoenergetic gamma rays are collimated into a narrow beam and if the detector behind the material only detects the gamma rays that passed through that material without any kind of interaction with this material, then the dependence should be simple exponential attenuation of gamma rays. Each of these interactions removes the photon from the beam either by absorbtion or by scattering away from the detector direction. Therefore the interactions can be characterized by a fixed probability of occurance per unit path length in the absorber. The sum of these probabilities is called the linear attenuation coefficient:

μ = τ(photoelectric) + σ(Compton) + κ(pair)

Linear Attenuation Coefficient

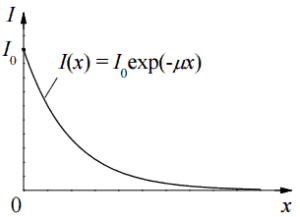

The attenuation of gamma radiation can be then described by the following equation.

I=I0.e-μx

, where I is intensity after attenuation, Io is incident intensity, μ is the linear attenuation coefficient (cm-1), and physical thickness of absorber (cm).

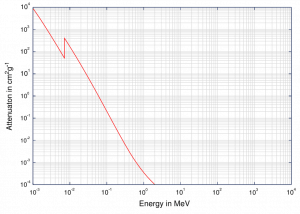

The materials listed in the table beside are air, water and a different elements from carbon (Z=6) through to lead (Z=82) and their linear attenuation coefficients are given for three gamma ray energies. There are two main features of the linear attenuation coefficient:

- The linear attenuation coefficient increases as the atomic number of the absorber increases.

- The linear attenuation coefficient for all materials decreases with the energy of the gamma rays.

Half Value Layer

The half value layer expresses the thickness of absorbing material needed for reduction of the incident radiation intensity by a factor of two. There are two main features of the half value layer:

- The half value layer decreases as the atomic number of the absorber increases. For example 35 m of air is needed to reduce the intensity of a 100 keV gamma ray beam by a factor of two whereas just 0.12 mm of lead can do the same thing.

- The half value layer for all materials increases with the energy of the gamma rays. For example from 0.26 cm for iron at 100 keV to about 1.06 cm at 500 keV.

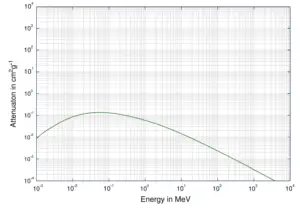

Mass Attenuation Coefficient

When characterizing an absorbing material, we can use sometimes the mass attenuation coefficient. The mass attenuation coefficient is defined as the ratio of the linear attenuation coefficient and absorber density (μ/ρ). The attenuation of gamma radiation can be then described by the following equation:

I=I0.e-(μ/ρ).ρl

, where ρ is the material density, (μ/ρ) is the mass attenuation coefficient and ρ.l is the mass thickness. The measurement unit used for the mass attenuation coefficient cm2g-1.

For intermediate energies the Compton scattering dominates and different absorbers have approximately equal mass attenuation coefficients. This is due to the fact that cross section of Compton scattering is proportional to the Z (atomic number) and therefore the coefficient is proportional to the material density ρ. At small values of gamma ray energy or at high values of gamma ray energy, where the coefficient is proportional to higher powers of the atomic number Z (for photoelectric effect σf ~ Z5; for pair production σp ~ Z2), the attenuation coefficient μ is not a constant.

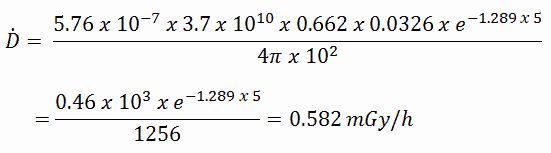

Example:

How much water schielding do you require, if you want to reduce the intensity of a 500 keV monoenergetic gamma ray beam (narrow beam) to 1% of its incident intensity? The half value layer for 500 keV gamma rays in water is 7.15 cm and the linear attenuation coefficient for 500 keV gamma rays in water is 0.097 cm-1.

The question is quite simple and can be described by following equation:

If the half value layer for water is 7.15 cm, the linear attenuation coefficient is:

Now we can use the exponential attenuation equation:

therefore

So the required thickness of water is about 47.5 cm. This is relatively large thickness and it is caused by small atomic numbers of hydrogen and oxygen. If we calculate the same problem for lead (Pb), we obtain the thickness x=2.8cm.

Linear Attenuation Coefficients

Table of Linear Attenuation Coefficients (in cm-1) for a different materials at gamma ray energies of 100, 200 and 500 keV.

| Absorber | 100 keV | 200 keV | 500 keV |

| Air | 0.000195/cm | 0.000159/cm | 0.000112/cm |

| Water | 0.167/cm | 0.136/cm | 0.097/cm |

| Carbon | 0.335/cm | 0.274/cm | 0.196/cm |

| Aluminium | 0.435/cm | 0.324/cm | 0.227/cm |

| Iron | 2.72/cm | 1.09/cm | 0.655/cm |

| Copper | 3.8/cm | 1.309/cm | 0.73/cm |

| Lead | 59.7/cm | 10.15/cm | 1.64/cm |

Half Value Layers

Table of Half Value Layers (in cm) for a different materials at gamma ray energies of 100, 200 and 500 keV.

| Absorber | 100 keV | 200 keV | 500 keV |

| Air | 3555 cm | 4359 cm | 6189 cm |

| Water | 4.15 cm | 5.1 cm | 7.15 cm |

| Carbon | 2.07 cm | 2.53 cm | 3.54 cm |

| Aluminium | 1.59 cm | 2.14 cm | 3.05 cm |

| Iron | 0.26 cm | 0.64 cm | 1.06 cm |

| Copper | 0.18 cm | 0.53 cm | 0.95 cm |

| Lead | 0.012 cm | 0.068 cm | 0.42 cm |

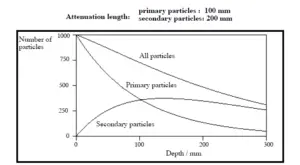

Validity of Exponential Law

The exponential law will always describe the attenuation of the primary radiation by matter. If secondary particles are produced

or if the primary radiation changes its energy or direction, then the effective attenuation will be much less. The radiation will penetrate more deeply into matter than is

predicted by the exponential law alone. The processmust be taken into account when

evaluating the effect of radiation shielding.

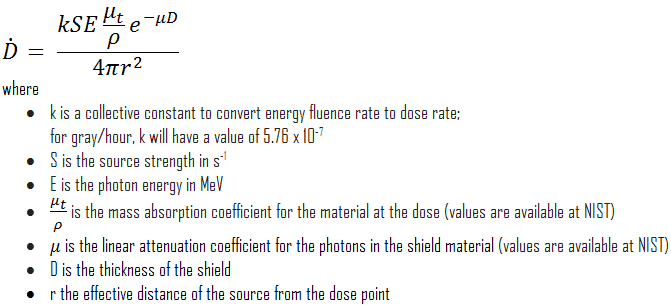

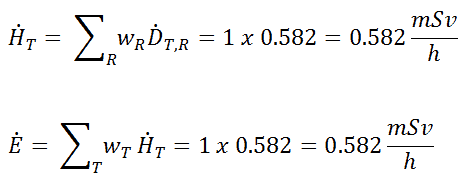

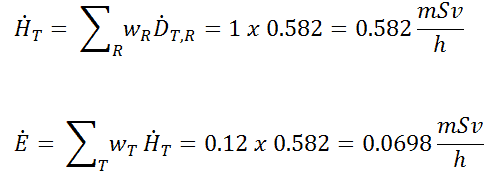

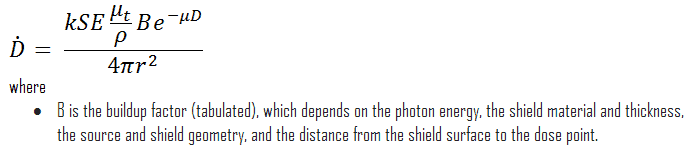

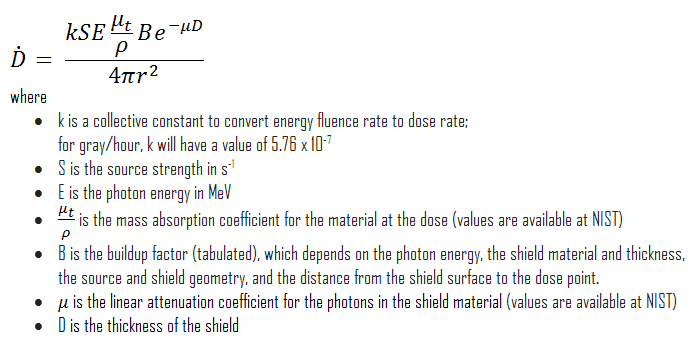

Buildup Factors for Gamma Rays Shielding

The buildup factor is a correction factor that considers the influence of the scattered radiation plus any secondary particles in the medium during shielding calculations. If we want to account for the buildup of secondary radiation, then we have to include the buildup factor. The buildup factor is then a multiplicative factor which accounts for the response to the uncollided photons so as to include the contribution of the scattered photons. Thus, the buildup factor can be obtained as a ratio of the total dose to the response for uncollided dose.

The extended formula for the dose rate calculation is:

The ANSI/ANS-6.4.3-1991 Gamma-Ray Attenuation Coefficients and Buildup Factors for Engineering Materials Standard, contains derived gamma-ray attenuation coefficients and buildup factors for selected engineering materials and elements for use in shielding calculations (ANSI/ANS-6.1.1, 1991).

We hope, this article, Gamma Ray / Gamma Radiation, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about radiation and dosimeters.