Basics of Nuclear Fission

Youtube animation

Principles of Nuclear Fission

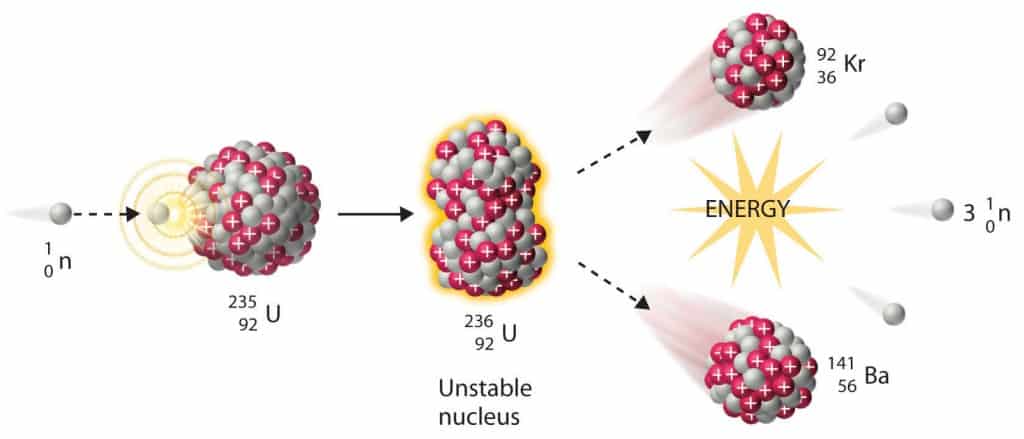

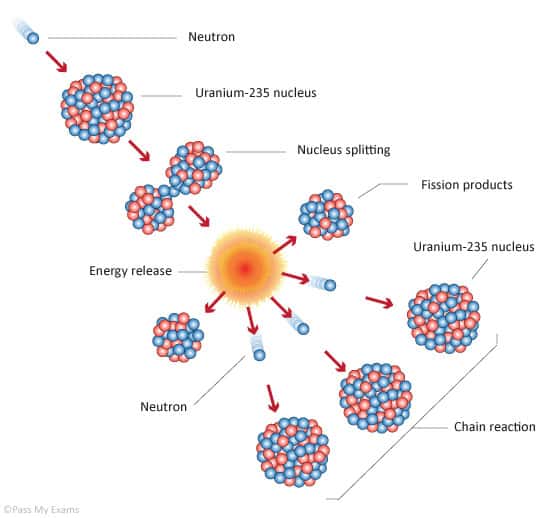

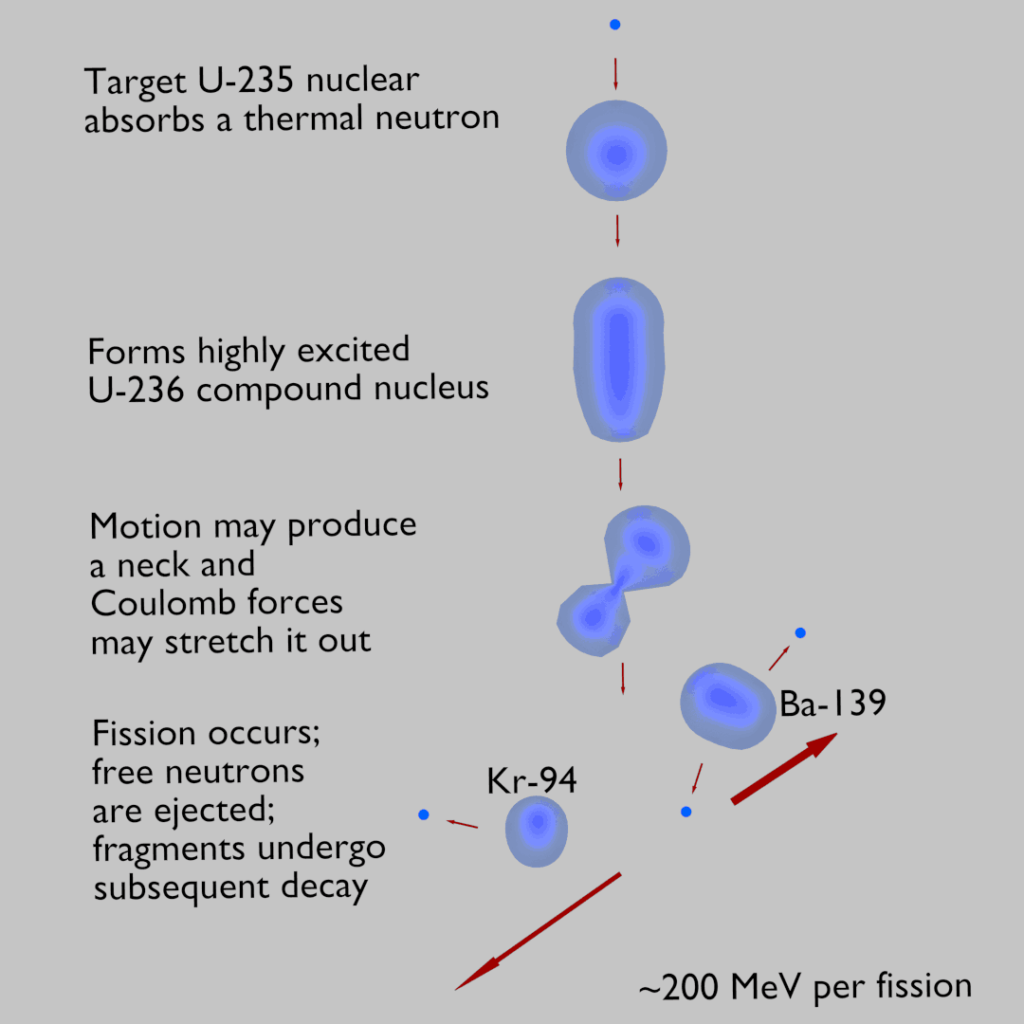

In general, the neutron-induced fission reaction is the reaction, in which the incident neutron enters the heavy target nucleus (fissionable nucleus), forming a compound nucleus that is excited to such a high energy level (Eexcitation > Ecritical) that the nucleus splits into two large fission fragments. A large amount of energy is released in the form of radiation and fragment kinetic energy. Moreover and what is crucial, the fission process may produce 2, 3 or more free neutrons and these neutrons can trigger further fission and a chain reaction can take place. In order to understand the process of fission, we must understand processes, that occur inside the nucleus to be fissioned. At first, the nuclear binding energy must be defined.

Nuclear Binding Energy

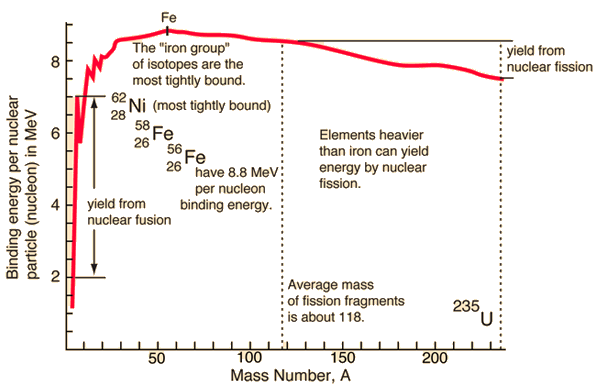

Source: hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu

During the nuclear splitting or nuclear fusion, some of the mass of the nucleus gets converted into huge amounts of energy and thus this mass is removed from the total mass of the original particles, and the mass is missing in the resulting nucleus. The nuclear binding energies are enormous, they are on the order of a million times greater than the electron binding energies of atoms.

For a nucleus with A (mass number) nucleons, the binding energy per nucleon Eb/A can be calculated. This calculated fraction is shown in the chart as a function of them mass number A. As can be seen, for low mass numbers Eb/A increases rapidly and reaches a maximum of 8.8 MeV at approximately A=60. The nuclei with the highest binding energies, that are most tightly bound belong to the “iron group” of isotopes (56Fe, 58Fe, 62Ni). After that, the binding energy per nucleon decreases. In the heavy nuclei (A>60) region, a more stable configuration is obtained, when a heavy nucleus splits into two lighter nuclei. This is the origin of the fission process. It may seem that all the heavy nuclei may undergo fission or even spontaneous fission. In fact, for all nuclei with atomic number greater than about 60, fission occurs very rarely. In order to fission process to take place, a sufficient amount of energy must be added to the nucleus and no matter how. The energetics and binding energies of certain nucleus are well described by the Liquid Drop Model, which examines the global properties of nuclei.

Liquid Drop Model

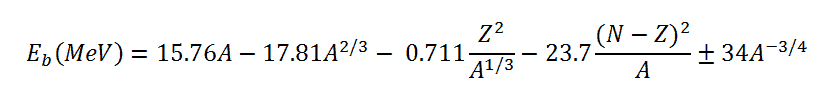

One of the first models which could describe very well the behavior of the nuclear binding energies and therefore of nuclear masses was the mass formula of von Weizsaecker (also called the semi-empirical mass formula – SEMF), that was published in 1935 by German physicist Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker. This theory is based on the liquid drop model proposed by George Gamow.

One of the first models which could describe very well the behavior of the nuclear binding energies and therefore of nuclear masses was the mass formula of von Weizsaecker (also called the semi-empirical mass formula – SEMF), that was published in 1935 by German physicist Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker. This theory is based on the liquid drop model proposed by George Gamow.

According to this model, the atomic nucleus behaves like the molecules in a drop of liquid. But in this nuclear scale, the fluid is made of nucleons (protons and neutrons), which are held together by the strong nuclear force. The liquid drop model of the nucleus takes into account the fact that the nuclear forces on the nucleons on the surface are different from those on nucleons in the interior of the nucleus. The interior nucleons are completely surrounded by other attracting nucleons. Here is the analogy with the forces that form a drop of liquid.

In the ground state the nucleus is spherical. If the sufficient kinetic or binding energy is added, this spherical nucleus may be distorted into a dumbbell shape and then may be splitted into two fragments. Since these fragments are a more stable configuration, the splitting of such heavy nuclei must be accompanied by energy release. This model does not explain all the properties of the atomic nucleus, but does explain the predicted nuclear binding energies.

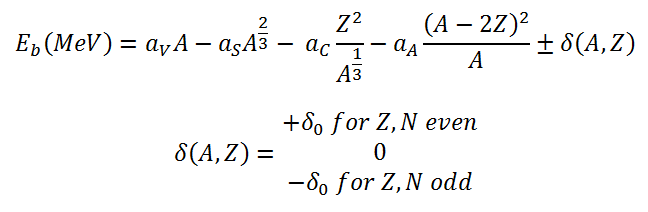

The nuclear binding energy as a function of the mass number A and the number of

protons Z based on the liquid drop model can be written as:

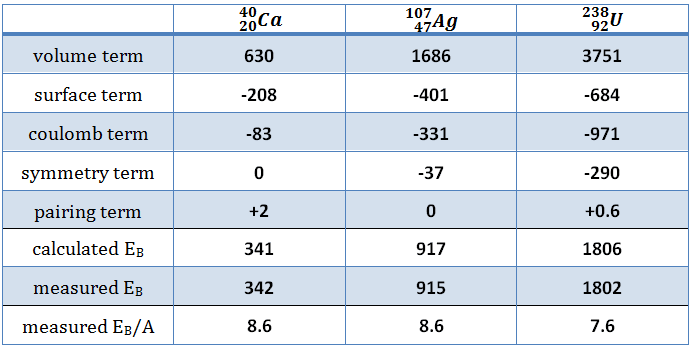

This formula is called the Weizsaecker Formula (or the semi-empirical mass formula). The physical meaning of this equation can be discussed term by term.

In order to calculate the binding energy, the coefficients aV, aS, aC, aA and aP must be known. The coefficients have units of megaelectronvolts (MeV) and are calculated by fitting to experimentally measured masses of nuclei. They usually vary depending on the fitting methodology. According to ROHLF, J. W., Modern Physics from α to Z0 , Wiley, 1994., the coefficients in the equation are following:

Using the Weizsaecker formula, also the mass of an atomic nucleus can be derived and is given by:

m = Z.mp +N.mn -Eb/c2

where mp and mn are the rest mass of a proton and a neutron, respectively, and Eb is the nuclear binding energy of the nucleus.

From the nuclear binding energy curve and from the table it can be seen that, in the case of splitting a 235U nucleus into two parts, the binding energy of the fragments (A ≈ 120) together is larger than that of the original 235U nucleus.

According to the Weizsaecker formula, the total energy released for such reaction will be approximately 235 x (8.5 – 7.6) ≈ 200 MeV.

See also: Liquid Drop Model

Critical Energy – Threshold Energy for Fission

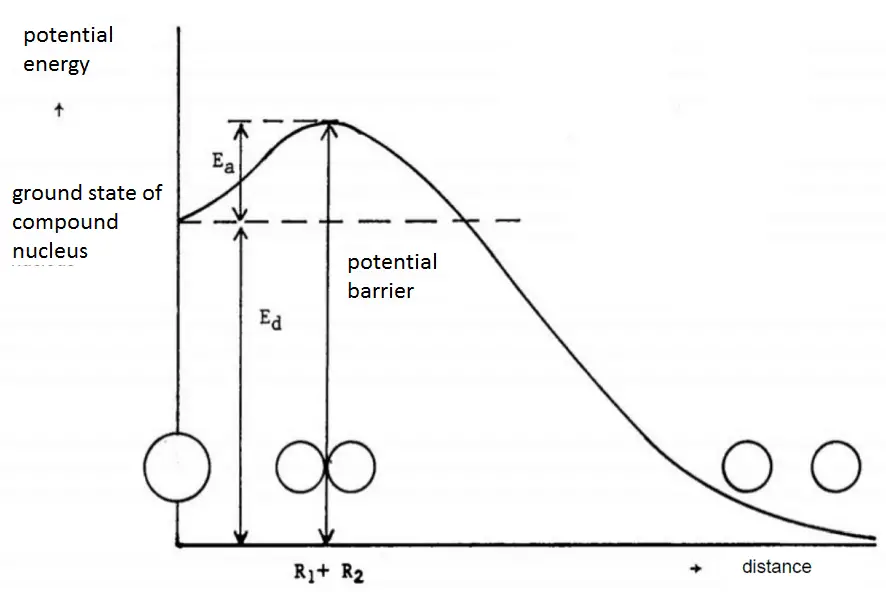

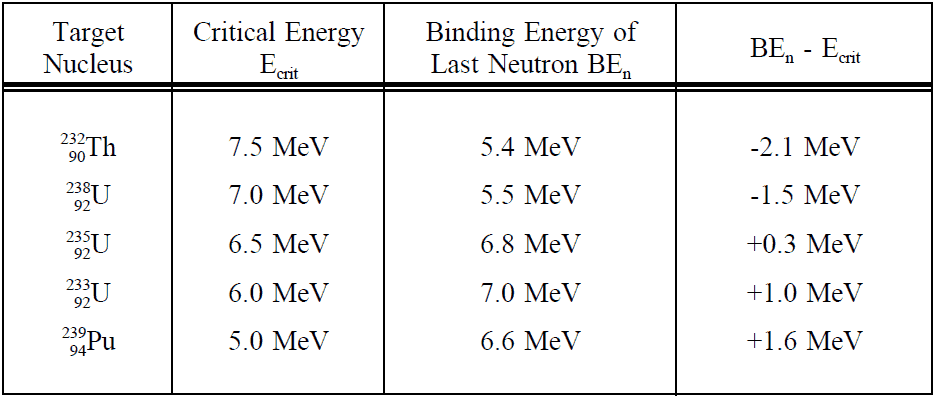

In principle, any nucleus, if brought into sufficiently high excited state, can be splitted. For fission to occur, the excitation energy must be above a particular value for certain nuclide. The minimum excitation energy required for fission to occur is known as the critical energy (Ecrit) or threshold energy.

The critical energy depends on the nuclear structure and is quite large for light nuclei with Z < 90. For heavier nuclei with Z > 90, the critical energy is about 4 to 6 MeV for A-even nuclei, and generally is much lower for A-odd nuclei. It must be noted, some heavy nuclei (eg. 240Pu or 252Cf) exhibit fission even in the ground state (without externally added excitation energy). This phenomena is known as the spontaneous fission. This process occur without the addition of the critical energy by the quantum-mechanical process of quantum tunneling through the Coulomb barrier (similarly like alpha particles in the alpha decay). The spontaneous fission contributes to ensure sufficient neutron flux on source range detectors when reactor is subcritical in long term shutdown.

Energy Release from Fission

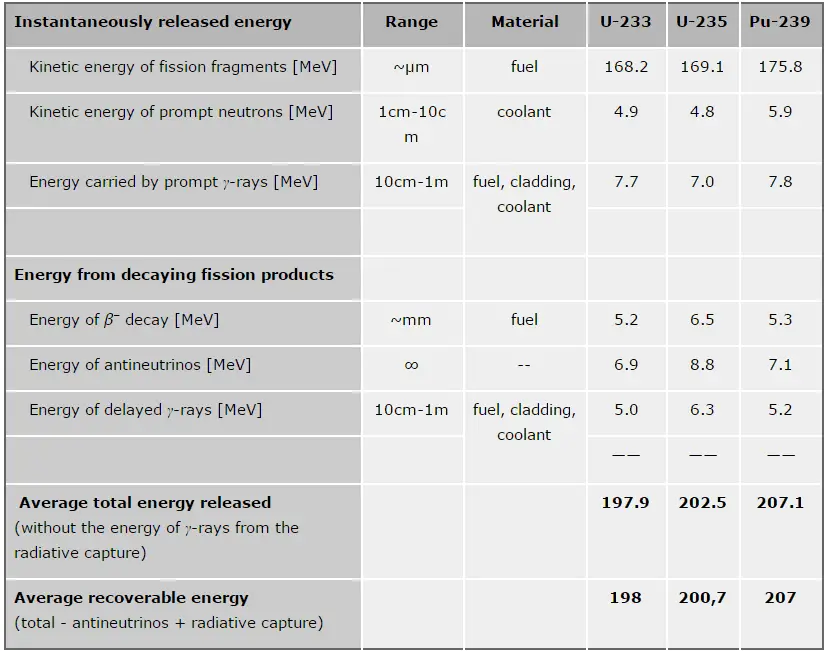

In general, the nuclear fission results in the release of enormous quantities of energy. The amount of energy depends strongly on the nucleus to be fissioned and also depends strongly on the kinetic energy of an incident neutron. In order to calculate the power of a reactor, it is necessary to be able precisely identify the individual components of this energy. At first, it is important to distinguish between the total energy released and the energy that can be recovered in a reactor.

The total energy released in fission can be calculated from binding energies of initial target nucleus to be fissioned and binding energies of fission products. But not all the total energy can be recovered in a reactor. For example, about 10 MeV is released in the form of neutrinos (in fact antineutrinos). Since the neutrinos are weakly interacting (with extremely low cross-section of any interaction), they do not contribute to the energy that can be recovered in a reactor.

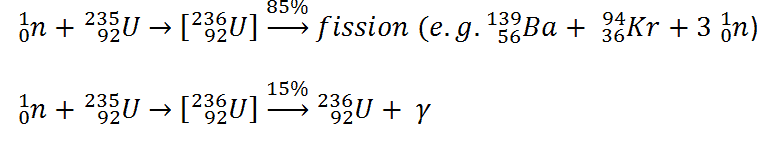

In order to understand this issue, we have to first investigate a typical fission reaction such as the one listed below.

Using this picture, we can identify and also describe almost all the individual components of the total energy energy released during the fission reaction.

The total energy released in a reactor is about 210 MeV per 235U fission, distributed as shown in the table. In a reactor, the average recoverable energy per fission is about 200 MeV, being the total energy minus the energy of the energy of antineutrinos that are radiated away. This means that about 3.1⋅1010 fissions per second are required to produce a power of 1 W. Since 1 gram of any fissile material contains about 2.5 x 1021 nuclei, the fissioning of 1 gram of fissile material yields about 1 megawatt-day (MWd) of heat energy.

The total energy released in a reactor is about 210 MeV per 235U fission, distributed as shown in the table. In a reactor, the average recoverable energy per fission is about 200 MeV, being the total energy minus the energy of the energy of antineutrinos that are radiated away. This means that about 3.1⋅1010 fissions per second are required to produce a power of 1 W. Since 1 gram of any fissile material contains about 2.5 x 1021 nuclei, the fissioning of 1 gram of fissile material yields about 1 megawatt-day (MWd) of heat energy.

As can be seen from the description of the individual components of the total energy energy released during the fission reaction, there is significant amount of energy generated outside the nuclear fuel (outside fuel rods). Especially the kinetic energy of prompt neutrons is largely generated in the coolant (moderator). This phenomena needs to be included in the nuclear calculations.

For LWR, it is generally accepted that about 2.5% of total energy is recovered in the moderator. This fraction of energy depends on the materials, their arrangement within the reactor, and thus on the reactor type.

Fission Fragments – Products of Nuclear Fission

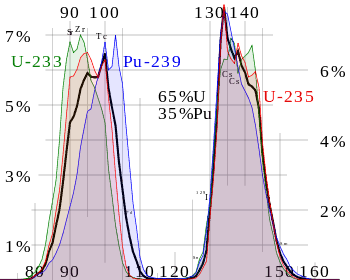

Nuclear fission fragments are the fragments left after a nucleus fissions. Typically, when uranium 235 nucleus undergoes fission, the nucleus splits into two smaller nuclei, along with a few neutrons and release of energy in the form of heat (kinetic energy of the these fission fragments) and gamma rays. The average of the fragment mass is about 118, but very few fragments near that average are found. It is much more probable to break up into unequal fragments, and the most probable fragment masses are around mass 95 (Krypton) and 137 (Barium).

Most of these fission fragments are highly unstable (radioactive) and undergo further radioactive decays to stabilize itself. Fission fragments interact strongly with the surrounding atoms or molecules traveling at high speed, causing them to ionize.

See also: Interaction of Heavy Charged Particles with Matter

Prompt and Delayed Neutrons

It is known the fission neutrons are of importance in any chain-reacting system. Neutrons trigger the nuclear fission of some nuclei (235U, 238U or even 232Th). What is crucial the fission of such nuclei produces 2, 3 or more free neutrons.

But not all neutrons are released at the same time following fission. Even the nature of creation of these neutrons is different. From this point of view we usually divide the fission neutrons into two following groups:

- Prompt Neutrons. Prompt neutrons are emitted directly from fission and they are emitted within very short time of about 10-14 second.

- Delayed Neutrons. Delayed neutrons are emitted by neutron rich fission fragments that are called the delayed neutron precursors. These precursors usually undergo beta decay but a small fraction of them are excited enough to undergo neutron emission. The fact the neutron is produced via this type of decay and this happens orders of magnitude later compared to the emission of the prompt neutrons, plays an extremely important role in the control of the reactor.

See also: Prompt Neutrons

See also: Delayed Neutrons

See also: Reactor control with and without delayed neutrons – Interactive chart

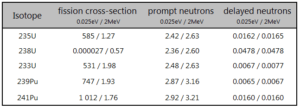

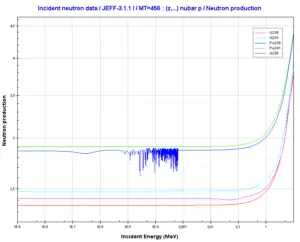

Source: JANIS (Java-based Nuclear Data Information Software); The JEFF-3.1.1 Nuclear Data Library

Key Characteristics of Prompt Neutrons

- Prompt neutrons are emitted directly from fission and they are emitted within very short time of about 10-14 second.

- Most of the neutrons produced in fission are prompt neutrons – about 99.9%.

- For example a fission of 235U by thermal neutron yields 2.43 neutrons, of which 2.42 neutrons are prompt neutrons and 0.01585 neutrons are the delayed neutrons.

- The production of prompt neutrons slightly increase with incident neutron energy.

- Almost all prompt fission neutrons have energies between 0.1 MeV and 10 MeV.

- The mean neutron energy is about 2 MeV. The most probable neutron energy is about 0.7 MeV.

- In reactor design the prompt neutron lifetime (PNL) belongs to key neutron-physical characteristics of reactor core.

- Its value depends especially on the type of the moderator and on the energy of the neutrons causing fission.

- In an infinite reactor (without escape) prompt neutron lifetime is the sum of the slowing down time and the diffusion time.

- In LWRs the PNL increases with the fuel burnup.

- The typical prompt neutron lifetime in thermal reactors is on the order of 10-4 second.

- The typical prompt neutron lifetime in fast reactors is on the order of 10-7 second.

Key Characteristics of Delayed Neutrons

- The presence of delayed neutrons is perhaps most important aspect of the fission process from the viewpoint of reactor control.

- Delayed neutrons are emitted by neutron rich fission fragments that are called the delayed neutron precursors.

- These precursors usually undergo beta decay but a small fraction of them are excited enough to undergo neutron emission.

- The emission of neutron happens orders of magnitude later compared to the emission of the prompt neutrons.

- About 240 n-emitters are known between 8He and 210Tl, about 75 of them are in the non-fission region.

- In order to simplify reactor kinetic calculations it is suggested to group together the precursors based on their half-lives.

- Therefore delayed neutrons are traditionally represented by six delayed neutron groups.

- Neutrons can be produced also in (γ, n) reactions (especially in reactors with heavy water moderator) and therefore they are usually referred to as photoneutrons. Photoneutrons are usually treated no differently than regular delayed neutrons in the kinetic calculations.

- The total yield of delayed neutrons per fission, vd, depends on:

- Isotope, that is fissioned.

- Energy of a neutron that induces fission.

- Variation among individual group yields is much greater than variation among group periods.

- In reactor kinetic calculations it is convenient to use relative units usually referred to as delayed neutron fraction (DNF).

- At the steady state condition of criticality, with keff = 1, the delayed neutron fraction is equal to the precursor yield fraction β.

- In LWRs the β decreases with fuel burnup. This is due to isotopic changes in the fuel.

- Delayed neutrons have initial energy between 0.3 and 0.9 MeV with an average energy of 0.4 MeV.

- Depending on the type of the reactor, and their spectrum, the delayed neutrons may be more (in thermal reactors) or less effective than prompt neutrons (in fast reactors). In order to include this effect into the reactor kinetic calculations the effective delayed neutron fraction – βeff must be defined.

- The effective delayed neutron fraction is the product of the average delayed neutron fraction and the importance factor βeff = β . I.

- The weighted delayed generation time is given by τ = ∑iτi . βi / β = 13.05 s, therefore the weighted decay constant λ = 1 / τ ≈ 0.08 s-1.

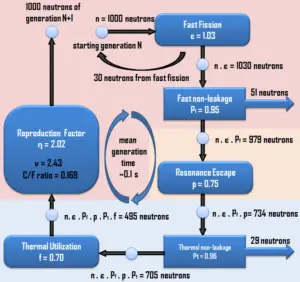

- The mean generation time with delayed neutrons is about ~0.1 s, rather than ~10-5 as in section Prompt Neutron Lifetime, where the delayed neutrons were omitted.

- Their presence completely changes the dynamic time response of a reactor to some reactivity change, making it controllable by control systems such as the control rods.

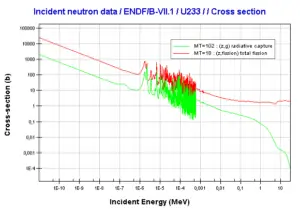

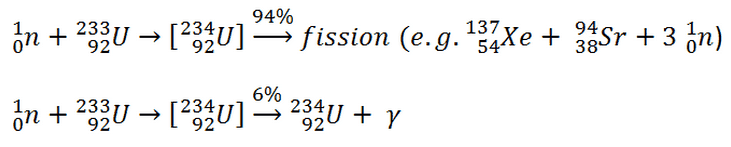

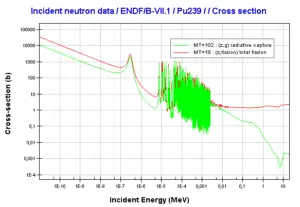

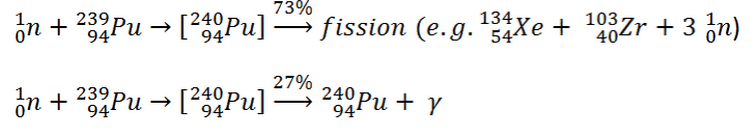

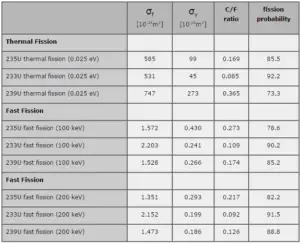

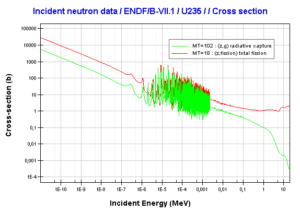

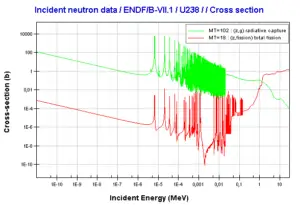

Capture-to-Fission Ratio

The probability that a neutron that is absorbed in a fissile nuclide causes a

fission is very important parameter of each fissile isotope. In terms of cross-sections, this probability is defined as:

σf / (σf + σγ) = 1 / (1 + σγ/σf) = 1 / (1 + α),

where α = σγ/σf is referred to as the capture-to-fission ratio. The capture-to-fission ratio may be used as an indicator of “quality” of fissile isotopes. The lower C/F ratio simply means that an absorption reaction will result in the fission rather than in the radiative capture. The ratio depends strongly on the incident neutron energy. In the fast neutron region, C/F ratio decreases. It is determined by the steeper decrease in radiative capture cross-section (see chart).

For 235U and 233U the thermal neutron capture-to-fission ratios are typically lower than those for fast neutrons (for mean energy of about 100 keV). It must be noted, the neutron flux of most fast reactors tends to peak around 200 keV, but the mean energy is between 100-200 keV depending on certain reactor design.

Further increase in neutron energy causes conversely a decrease in C/F ratio. This is not the case of 239Pu, for 100 keV neutrons, the C/F ratio is lower than for thermal neutrons. For the fissile isotopes (233U, 235U and 239Pu), a small capture-to-fission ratio is an advantage, because neutrons captured onto them are lost.

Nuclear Fission Chain Reaction

The chain reaction can take place only in the proper multiplication environment and only under proper conditions. It is obvious, if one neutron causes two further fissions, the number of neutrons in the multiplication system will increase in time and the reactor power (reaction rate) will also increase in time. In order to stabilize such multiplication environment, it is necessary to increase the non-fission neutron absorption in the system (e.g. to insert control rods). Moreover, this multiplication environment (nuclear reactor) behaves like the exponential system, that means the power increase is not linear, but it is exponential.

The chain reaction can take place only in the proper multiplication environment and only under proper conditions. It is obvious, if one neutron causes two further fissions, the number of neutrons in the multiplication system will increase in time and the reactor power (reaction rate) will also increase in time. In order to stabilize such multiplication environment, it is necessary to increase the non-fission neutron absorption in the system (e.g. to insert control rods). Moreover, this multiplication environment (nuclear reactor) behaves like the exponential system, that means the power increase is not linear, but it is exponential.

On the other hand, if one neutron causes less than one further fission, the number of neutrons in the multiplication system will decrease in time and the reactor power (reaction rate) will also decrease in time. In order to sustain the chain reaction, it is necessary to decrease the non-fission neutron absorption in the system (e.g. to withdraw control rods).

In fact, there is always a competition for the fission neutrons in the multiplication environment, some neutrons will cause further fission reaction, some will be captured by fuel materials or non-fuel materials and some will leak out of the system.

In order to describe the multiplication system, it is necessary to define the infinite and finite multiplication factor of a reactor. The method of calculations of multiplication factors has been developed in the early years of nuclear energy and is only applicable to thermal reactors, where the bulk of fission reactions occurs at thermal energies. This method well puts into the context all the processes, that are associated with the thermal reactors (e.g. the neutron thermalisation, the neutron diffusion or the fast fission), because the most important neutron-physical processes occur in energy regions that can be clearly separated from each other. In short, the calculation of multiplication factor gives a good insight in the processes that occur in each thermal multiplying system.

Distinction between Fissionable, Fissile and Fertile

In nuclear engineering, fissionable material (nuclide) is material that is capable of undergoing fission reaction after absorbing either thermal (slow or low energy) neutron or fast (high energy) neutron. Fissionable materials are a superset of fissile materials. Fissionable materials also include an isotope 238U that can be fissioned only with high energy (>1MeV) neutron. These materials are used to fuel thermal nuclear reactors, because they are capable of sustaining a nuclear fission chain reaction.

Fissile materials undergoes fission reaction after absorption of the binding energy of thermal neutron. They do not require additional kinetic energy for fission. If the neutron has higher kinetic energy, this energy will be transformed into additional excitation energy of the compound nucleus. On the other hand, the binding energy released by compound nucleus of (238U + n) after absorption of thermal neutron is less than the critical energy, so the fission reaction cannot occur. The distinction is described in the following points.

- Fissile materials are a subset of fissionable materials.

- Fissionable material consist of isotopes that are capable of undergoing nuclear fission after capturing either fast neutron (high energy neutron – let say >1 MeV) or thermal neutron (low energy neutron – let say 0.025 eV). Typical fissionable materials: 238U, 240Pu, but also 235U, 233U, 239Pu, 241Pu

- Fissile material consist of fissionable isotopes that are capable of undergoing nuclear fission only after capturing a thermal neutron. 238U is not fissile isotope, because 238U cannot be fissioned by thermal neutron. 238U does not meet also alternative requirement to fissile materials. 238U is not capable of sustaining a nuclear fission chain reaction, because neutrons produced by fission of 238U have lower energies than original neutron (usually below the threshold energy of 1 MeV). Typical fissile materials: 235U, 233U, 239Pu, 241Pu.

- Fertile material consist of isotopes that are not fissionable by thermal neutrons, but can be converted into fissile isotopes (after neutron absorption and subsequent nuclear decay). Typical fertile materials: 238U, 232Th.

Fissile materials undergoes fission reaction after absorption of the binding energy of thermal neutron. They do not require additional kinetic energy for fission. If the neutron has higher kinetic energy, this energy will be transformed into additional excitation energy of the compound nucleus. On the other hand, the binding energy released by compound nucleus of (238U + n) after absorption of thermal neutron is less than the critical energy, so the fission reaction cannot occur. The distinction is described in the following points.

- Fissile materials are a subset of fissionable materials.

- Fissionable material consist of isotopes that are capable of undergoing nuclear fission after capturing either fast neutron (high energy neutron – let say >1 MeV) or thermal neutron (low energy neutron – let say 0.025 eV). Typical fissionable materials: 238U, 240Pu, but also 235U, 233U, 239Pu, 241Pu

- Fissile material consist of fissionable isotopes that are capable of undergoing nuclear fission only after capturing a thermal neutron. 238U is not fissile isotope, because 238U cannot be fissioned by thermal neutron. 238U does not meet also alternative requirement to fissile materials. 238U is not capable of sustaining a nuclear fission chain reaction, because neutrons produced by fission of 238U have lower energies than original neutron (usually below the threshold energy of 1 MeV). Typical fissile materials: 235U, 233U, 239Pu, 241Pu.

- Fertile material consist of isotopes that are not fissionable by thermal neutrons, but can be converted into fissile isotopes (after neutron absorption and subsequent nuclear decay). Typical fertile materials: 238U, 232Th.

See also: Neutron cross-section

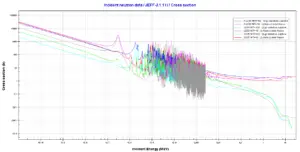

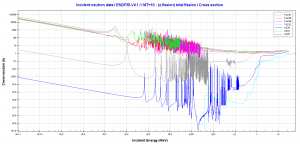

Comparison of cross-sections

Source: JANIS (Java-based nuclear information software) http://www.oecd-nea.org/janis/

http://www.oecd-nea.org/janis/

Fissile / Fertile Material Cross-sections. Comparison of total fission cross-sections.

Uranium 235. Comparison of total fission cross-section and cross-section for radiative capture.

Uranium 235. Comparison of total fission cross-section and cross-section for radiative capture.

http://www.oecd-nea.org/janis/

Uranium 238. Comparison of total fission cross-section and cross-section for radiative capture.

We hope, this article, Nuclear Fission, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about radiation and dosimeters.