Definition of Cross-section

In general, the cross-section is an effective area that quantifies the likelihood of certain interaction between an incident object and a target object. The cross-section of a particle is the same as the cross section of a hard object, if the probabilities of hitting them with a ray are the same.

In general, the cross-section is an effective area that quantifies the likelihood of certain interaction between an incident object and a target object. The cross-section of a particle is the same as the cross section of a hard object, if the probabilities of hitting them with a ray are the same.

For a given event, the cross section σ is given by

σ = μ/n

where

- σ is the cross-section of this event [m2],

- μ is the attenuation coefficient due to the occurrence of this event [m-1],

- n is the density of the target particles [m-3].

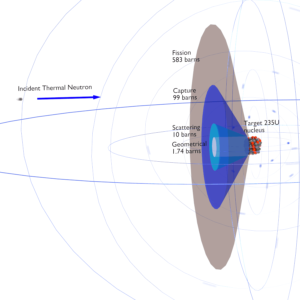

In nuclear physics, the nuclear cross section of a nucleus is commonly used to characterize the probability that a nuclear reaction will occur. The cross-section is typically denoted σ and measured in units of area [m2]. The standard unit for measuring a nuclear cross section is the barn, which is equal to 10−28 m² or 10−24 cm². It can be seen the concept of a nuclear cross section can be quantified physically in terms of “characteristic target area” where a larger area means a larger probability of interaction.

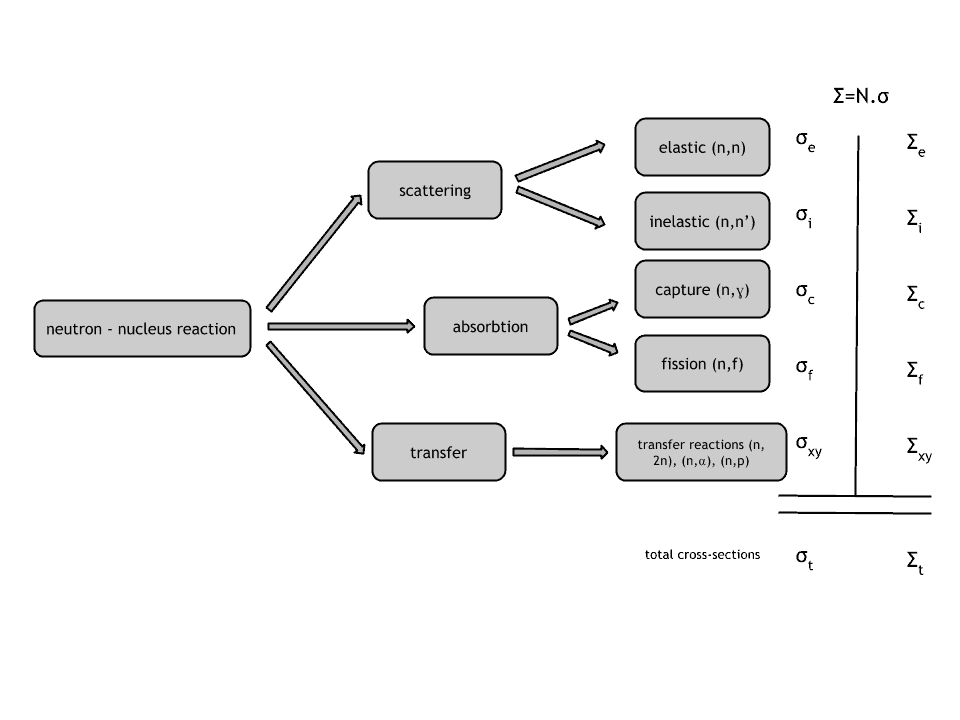

Microscopic Cross-section

The extent to which neutrons interact with nuclei is described in terms of quantities known as cross-sections. Cross-sections are used to express the likelihood of particular interaction between an incident neutron and a target nucleus. It must be noted this likelihood do not depend on real target dimensions. In conjunction with the neutron flux, it enables the calculation of the reaction rate, for example to derive the thermal power of a nuclear power plant. The standard unit for measuring the microscopic cross-section (σ-sigma) is the barn, which is equal to 10-28 m2. This unit is very small, therefore barns (abbreviated as “b”) are commonly used.

The cross-section σ can be interpreted as the effective ‘target area’ that a nucleus interacts with an incident neutron. The larger the effective area, the greater the probability for reaction. This cross-section is usually known as the microscopic cross-section.

The concept of the microscopic cross-section is therefore introduced to represent the probability of a neutron-nucleus reaction. Suppose that a thin ‘film’ of atoms (one atomic layer thick) with Na atoms/cm2 is placed in a monodirectional beam of intensity I0. Then the number of interactions C per cm2 per second will be proportional to the intensity I0 and the atom density Na. We define the proportionality factor as the microscopic cross-section σ:

σt = C/Na.I0

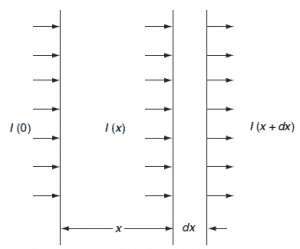

In order to be able to determine the microscopic cross section, transmission measurements are performed on plates of materials. Assume that if a neutron collides with a nucleus it will either be scattered into a different direction or be absorbed (without fission absorption). Assume that there are N (nuclei/cm3) of the material and there will then be N.dx per cm2 in the layer dx.

Only the neutrons that have not interacted will remain traveling in the x direction. This causes the intensity of the uncollided beam will be attenuated as it penetrates deeper into the material.

Then, according to the definition of the microscopic cross section, the reaction rate per unit area is Nσ Ι(x)dx. This is equal to the decrease of the beam intensity, so that:

-dI = N.σ.Ι(x).dx

and

Ι(x) = Ι0e-N.σ.x

It can be seen that whether a neutron will interact with a certain volume of material depends not only on the microscopic cross-section of the individual nuclei but also on the density of nuclei within that volume. It depends on the N.σ factor. This factor is therefore widely defined and it is known as the macroscopic cross section.

The difference between the microscopic and macroscopic cross sections is extremely important. The microscopic cross section represents the effective target area of a single nucleus, while the macroscopic cross section represents the effective target area of all of

the nuclei contained in certain volume.

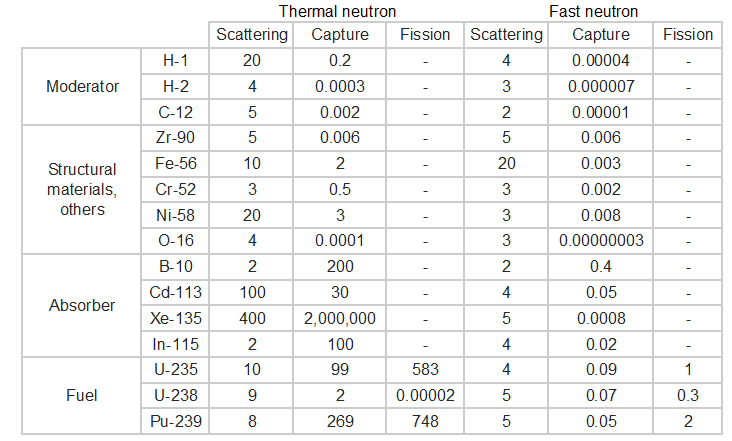

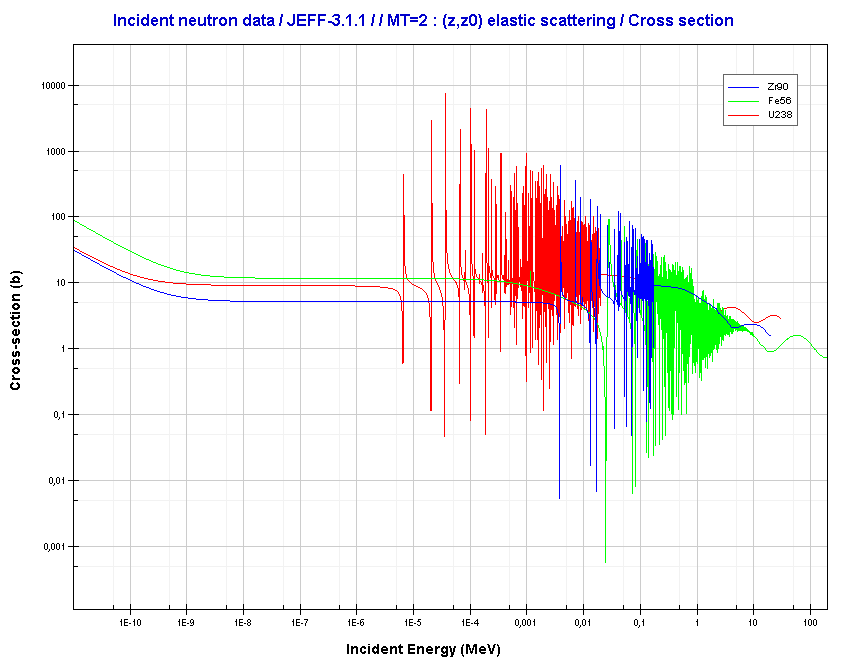

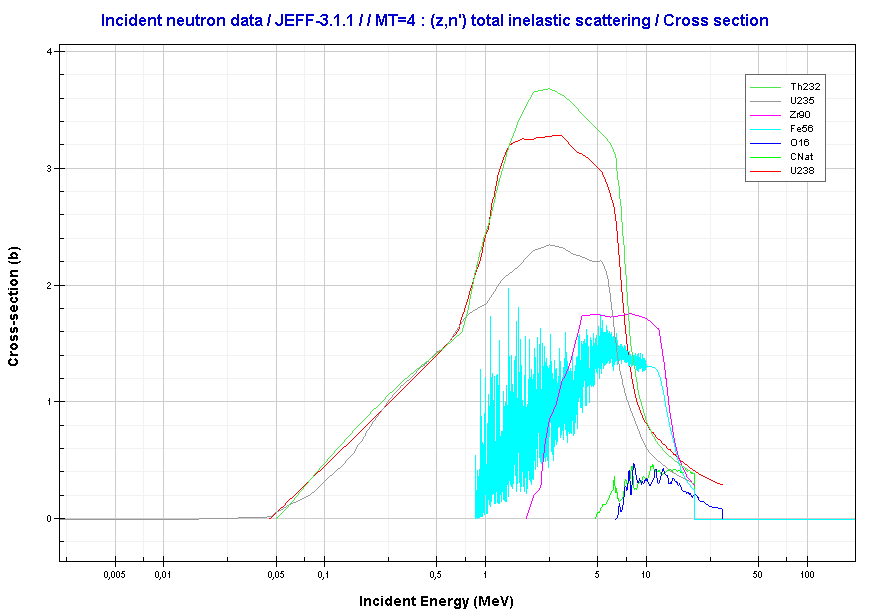

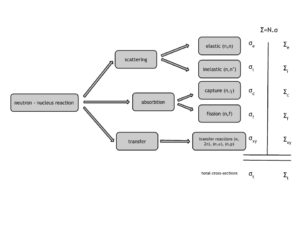

The neutron cross-section is variable and depends on:

- Target nucleus (hydrogen, boron, uranium, etc.). Each isotop has its own set of cross-sections.

- Type of the reaction (capture, fission, etc.). Cross-sections are different for each nuclear reaction.

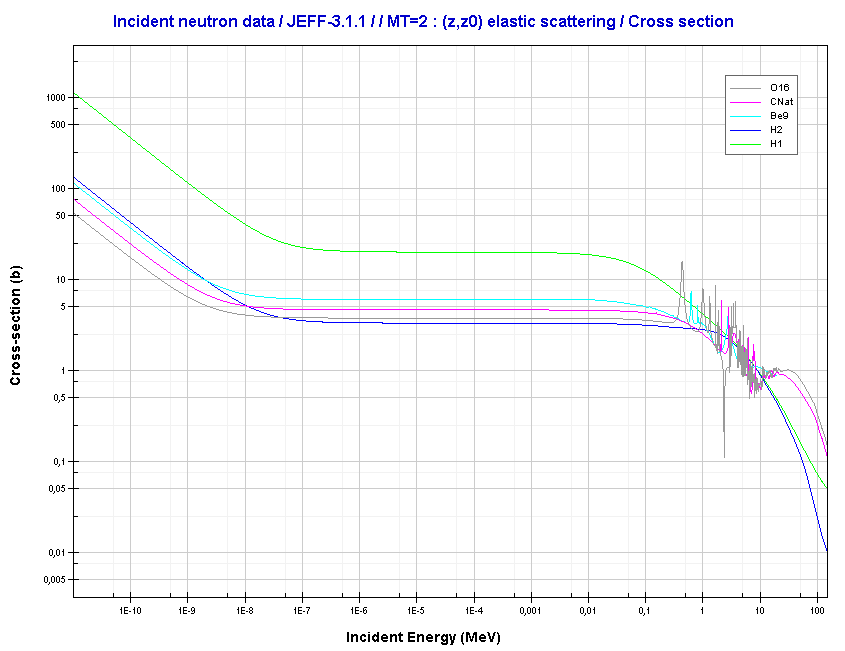

- Neutron energy (thermal neutron, resonance neutron, fast neutron). For a given target and reaction type, the cross-section is strongly dependent on the neutron energy. In the common case, the cross section is usually much larger at low energies than at high energies. This is why most nuclear reactors use a neutron moderator to reduce the energy of the neutron and thus increase the probability of fission, essential to produce energy and sustain the chain reaction.

- Target energy (temperature of target material – Doppler broadening). This dependency is not so significant, but the target energy strongly influences inherent safety of nuclear reactors due to a Doppler broadening of resonances.

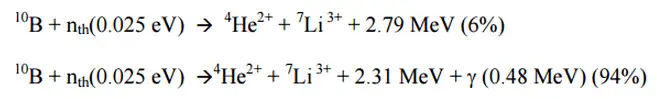

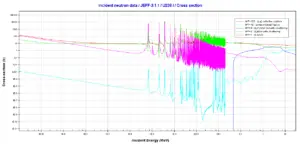

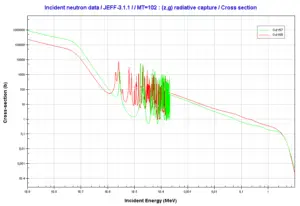

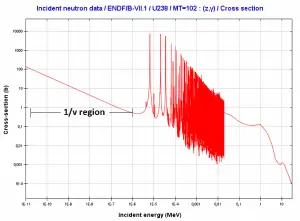

Microscopic cross-section varies with incident neutron energy. Some nuclear reactions exhibit very specific dependency on incident neutron energy. This dependency will be described on the example of the radiative capture reaction. The likelihood of a neutron radiative capture is represented by the radiative capture cross section as σγ. The following dependency is typical for radiative capture, it definitely does not mean, that it is typical for other types of reactions (see elastic scattering cross-section or (n,alpha) reaction cross-section).

The capture cross-section can be divided into three regions according to the incident neutron energy. These regions will be discussed separately.

- 1/v Region

- Resonance Region

- Fast Neutrons Region

Source: JANIS (Java-based Nuclear Data Information Software); The JEFF-3.1.1 Nuclear Data Library

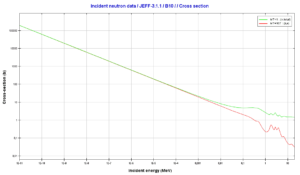

Source: JANIS 4.0

1/v Region

In the common case, the cross section is usually much larger at low energies than at high energies. For thermal neutrons (in 1/v region), also radiative capture cross-sections increase as the velocity (kinetic energy) of the neutron decreases. Therefore the 1/v Law can be used to determine shift in capture cross-section, if the neutron is in equilibrium with a surrounding medium. This phenomenon is due to the fact the nuclear force between the target nucleus and the neutron has a longer time to interact.

This law is aplicable only for absorbtion cross-section and only in the 1/v region.

Example of cross- sections in 1/v region:

The absorbtion cross-section for 238U at 20°C = 293K (~0.0253 eV) is:

.

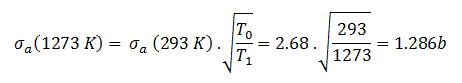

The absorbtion cross-section for 238U at 1000°C = 1273K is equal to:

This cross-section reduction is caused only due to the shift of temperature of surrounding medium.

Resonance Region

The largest cross-sections are usually at neutron energies, that lead to long-lived states of the compound nucleus. The compound nuclei of these certain energies are referred to as nuclear resonances and its formation is typical in the resonance region. The widths of the resonances increase in general with increasing energies. At higher energies the widths may reach the order of the distances between resonances and then no resonances can be observed. The narrowest resonances are usually compound states of heavy nuclei (such as fissionable nuclei).

Since the mode of decay of the compound nucleus does not depend on the way the compound nucleus was formed, the nucleus sometimes emits a gamma ray (radiative capture) or sometimes emits a neutron (scattering). In order to understand the way, how a nucleus will stabilize itself, we have to understand the behaviour of compound nucleus.

The compound nucleus emits a neutron only after one neutron obtains an energy in collision with other nucleon greater than its binding energy in the nucleus. It have some delay, because the excitation energy of the compound nucleus is divided among several nucleons. It is obvious the average time that elapses before a neutron can be emitted is much longer for nuclei with large number of nucleons than when only a few nucleons are involved. It is a consequence of sharing the excitation energy among a large number of nucleons.

This is the reason the radiative capture is comparatively unimportant in light nuclei but becomes increasingly important in the heavier nuclei.

It is obvious the compound states (resonances) are observed at low excitation energies. This is due to the fact, the energy gap between the states is large. At high excitation energy, the gap between two compound states is very small and the widths of resonances may reach the order of the distances between resonances. Therefore at high energies no resonances can be observed and the cross section in this energy region is continuous and smooth.

The lifetime of a compound nucleus is inversely proportional to its total width. Narrow resonances therefore correspond to capture while the wider resonances are due to scattering.

See also: Nuclear Resonance

Fast Neutrons Region

The radiative capture cross-section at energies above the resonance region drops rapidly to very small values. This rapid drop is caused by the compound nucleus, which is formed in more highly-excited states. In these highly-excited states it is more likely that one neutron obtains an energy in collision with other nucleon greater than its binding energy in the nucleus. The neutron emission becomes dominant and gamma decay becomes less important. Moreover, at high energies, the inelastic scattering and (n,2n) reaction are highly probable at the expense of both elastic scattering and radiative capture.

Doppler Broadening of Resonances

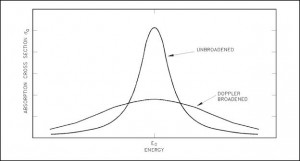

In general, Doppler broadening is the broadening of spectral lines due to the Doppler effect caused by a distribution of kinetic energies of molecules or atoms. In reactor physics a particular case of this phenomenon is the thermal Doppler broadening of the resonance capture cross sections of the fertile material (e.g. 238U or 240Pu) caused by thermal motion of target nuclei in the nuclear fuel.

The Doppler broadening of resonances is very important phenomenon, which improves reactor stability, because it accounts for the dominant part of the fuel temperature coefficient (the change in reactivity per degree change in fuel temperature) in thermal reactors and makes a substantial contribution in fast reactors as well. This coefficient is also called the prompt temperature coefficient because it causes an immediate response on changes in fuel temperature. The prompt temperature coefficient of most thermal reactors is negative.

See also: Doppler Broadening

We hope, this article, Microscopic Cross-section, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about radiation and dosimeters.